- Home

- Hamilton, Donald

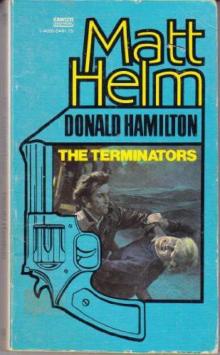

The Terminators Page 16

The Terminators Read online

Page 16

"None, Mr. Helm. Because she had no gun when they broke into the room." I started to speak and checked myself. After a moment, Greta went on: "By the greatest good luck for us, she'd lent her gun to your Captain Priest and he'd stepped out for a moment. We were watching, we saw him tucking it away as he came out of the room, and heard him thank her for the loan. Naturally, we grabbed the opportunity while he was gone—"

I drew a long, long breath. "Thanks, that's what I wanted to know. Just one more question. There were three men, one driving the car. Where'd the driver get to, since he doesn't seem to be around?"

She hesitated cautiously once more; then she laughed. "It doesn't matter now, I suppose. Papa has a good deal of respect for you, Mr. Helm; and while Aloco's Mr. Yale is still with him, I'm afraid he doesn't think much of Norman as a bodyguard. The third man had strict orders to come straight back, just in case you managed to escape the ambush here and went looking for Papa."

I grinned. "Nothing like a dangerous reputation, I always say. Well, let's go take a ride in a whirly-bird. . . ."

It was a relatively big machine to pull itself up by its own bootstraps—or lower itself down, as it was doing now. The only bigger ones I'd seen close up had had U.S. marked clearly on the fuselages. A private chopper this size, capable of carrying four people, would be worth somewhere around a million bucks; it would also be worth a lot of status in executive circles. But of course it wasn't a private chopper, at least not at the moment. Regardless of its civilian markings, it was operating on official U.S. government business. I couldn't help wondering just how our people had managed to promote such fancy airborne transportation in this chilly comer of the world, but that's the kind of question you never ask.

We waited clear of the spray and small stones driven out from under the machine as it settled to the rain-wet runway. Then the rotor slowed, just ticking over idly, and the door opened. I shoved the girl ahead, and hurried forward with her, ducking low although there was actually plenty of clearance under the big, slow-turning blades, even for a man of my height. Greta clambered through the doorway or hatch. When she was inside, I pulled myself up, and stopped, looking at a revolver aimed at my face.

"Welcome aboard, Eric," said Paul Denison.

XVIII.

IT was one of those moments. You know you've goofed, and goofed badly; and what the hell are you going to do about it—if anything?

I had my options, of course. I could hurl myself backwards onto the runway and, if I didn't knock my brains out, roll aside, make that lightning draw that had earned me worldwide renown—actually, we're supposed to be smart enough to have a weapon in hand when it's needed, and to hell with that fast-draw, jazz—and shoot it out heroically. The trouble was, I happened to know that Denison was an excellent marksman with very fast reflexes. If I did anything melodramatic, I'd hit the pavement dead if he wanted me dead And even if he missed, and I actually got a gun out, I wasn't quite certain that I wanted him dead, at least not yet. The crystal ball was still cloudy; and I wasn't sure it was that kind of a last-ditch situation, worth cluttering up the neighborhood with a lot of bloody stiffs, mine perhaps included.

There was, of course, the verbal option: I could tell him he couldn't get away with this, and what the hell did he think he was doing, and I'd get him for it if it was the last thing I did, and if I didn't Mac would see that he was properly terminated, immediately. However, I wasn't a Hollywood hero and there were no cameras or mikes aimed my way—just the lone Colt .38—so I didn't waste time being brave with my mouth.

I said, "The gun's under my belt. The knife's in my right-hand pants pocket. Do you get them, or do I?"

He grinned. "Good old matter-of-fact Eric." He reached out. "I'll take the gun. You get the knife. Division of labor. Okay?"

A moment later, minus both weapons, I was occupying the seat beside the pilot, a sandy-haired, moustached gent, who, like a lot of those fly-boys, didn't seem to figure guns and knives were any of his business. He just drove the airborne buggy and kept his mouth shut.

Behind me, Denison said, "Okay, Jerry, take this thing upstairs. Swing either north or south and get out of sight fast. There'll be a plane coming in from the coast shortly, and we'd rather they didn't see us, don't you know, old chap?"

I waited until the roar and clatter of takeoff had subsided and the air strip was receding into the mists behind us. Then I asked, "What's with this old-chap business, amigo?''

Denison chuckled. "Ah, hell, us glamorous mercenaries are all supposed to be dead-eye, stiff-upper-lip British types who used to shoot elephants for a living. Anyway, Gerald here is an old-chap type, and one kind of tends to mimic it, don't you know?"

"Up yours," said Jerry Gerald without turning his head.

"Well, he's picked up a little Yankee slang along the way." Out of the comer of my eye, I saw Denison glancing at the diminutive occupant of the seat to his left. Greta Elfenbem was sitting very still and keeping very quiet; she didn't give the impression of being happy with the situation. Denison said, "You seem to've switched girls since I last had you under surveillance, Eric."

"That's right."

"Left your partner to Elfenbein and took the daughter in trade, eh? Very neat. I figured you might pull something tricky like that. Happy to see you haven't lost your touch."

"I'm happy you're happy," I said. "Who talked?"

I was thinking of Rolf, reluctantly and of the grandmother who hated Sigmund. But Granny wouldn't have known enough about my arrangements to betray them to Denison unless Rolf had told her, deliberately or carelessly; so it came back to the friendly taxi driver, our man in Svolvaer.

"Nobody talked," Denison said. "Or, let's say, you did."

I glanced around quickly, maybe indignantly. He gestured with the revolver. I turned my head forward again. He laughed.

"Seven, eight, nine years ago, you talked," he said. "Don't you remember? You talked quite a bit, about getting into the mmd of the other man and looking at the situation through his eyes. Sitting at the Master's feet, I drank in his golden words, if that's what you do with golden words. Maybe you eat them."

"Go to hell," I said.

"In due time; don't rush me," Denison said cheerfully. "Another thing you said, another nugget of wisdom I've treasured through the years, is that if there's only one logical thing for a man to do, and he's a logical man, you can probably gamble safely on his doing it. Consider this morning, Eric. You're certainly a logical fellow; and there you'd be, I figured, with all that valuable data. . . . Oh, let's have it, if you don't mind. The valuable data."

"Be my guest," I said. I took the three envelopes from my inside pocket, held them back over my shoulder, and felt them taken away. "Do you read scientific Norwegian?" I asked.

"I read neither scientific nor Norwegian," Denison said. "But L. A. does. He sat down and learned it when he got involved with Torbotten. He's not really stupid, you know, just because he's heard that bald men are supposed to be virile, and because he shuns public appearances, and has all that money. Anyway, my job is to deliver, not decipher. I'll let him figure it out."

There was a little pause while the helicopter cruised high over a maze of islands and rocky reefs against which the gray Arctic sea broke sullenly. We'd swung north, and I wondered if we'd come as far as Altafjord where the Tirpitz was sunk. The minisubs sneaked in and crippled her, and the planes finally finished her off, but it wasn't easy. But we probably weren't that far up the coast.

I'd have been just as happy to sit watching the watery scenery roll away below us in silence—well, silence except for the steady racket of the machinery. I didn't feel much like talking. You don't after you're made a bad booboo. Denison, however, was obviously in a euphoric, chatty mood, and there were things I didn't know that I wanted to know, and guesses I'd made that I wanted confirmed. I couldn't afford to pass up the opportunity.

"You were telling me how smart you were," I said, to start him going again.

"Well, as I was

saying," he responded readily, "there you were with all that valuable data, on the edge of an island airport with hostiles all around you. Would you be stupid enough, under constant threat of attack, to hold to the original schedule and wait over twelve hours for the ferry to the mainland—oh, yes, your plans are common knowledge, thanks to a few bucks and Mr. Norman Yale who got them, I gather, by virtue of a few bucks and a traitor in your ranks named Wetherill. Well, standing by an airstrip, would you call for a taxi, a boat, a horse, or a snowmobile? No, I decided after careful consideration, a logical chap like you would do none of those things. You'd send for an airplane. Clever, huh?"

"Brilliant," I said.

"And when would you schedule it?" Denison asked rhetorically. "Well, the drop was set, I gathered—both drops were set—rather loosely for the first convenient time after the ship was seen to dock. It was up to the contact to keep track of its arrival. That took care of possible delays due to fog or breakdowns. In Svolvaer, I didn't figure the evening when you arrived would be considered convenient. Your boy wasn't the kind of hero, I'd been told, who'd like playing tag in the dark. The morning, then, as soon as it was light enough for him to feel safe. Okay so far?"

"Right on, man," I said.

"So I checked some celestial tables and found that first daylight was some time after five, but with the usual lousy weather around here it probably wouldn't really be light until six or six-thirty. Okay. You'd want to give yourself some leeway. If your man was late arriving with the merchandise, you wouldn't want to have that bird circling overhead impatiently, maybe scaring him away. Say you'd give yourself a full hour or a little more; that meant you'd have your plane arriving at seven-thirty or eight. But there was a strong possibility, actually, that your contact would want to get the damned drop over with as quickly as possible after visibility allowed. I took a chance, and came in forty-five minutes ahead of the earliest time I figured your plane would be due, gambling that you'd already have your business transacted, and that you'd be anxious enough to get away that you wouldn't be suspicious of a little discrepancy in timing.. .."

That was the trouble, of course. I'd had plenty of warning. It had been the wrong kind of aircraft at the wrong time; and my subconscious had been nagging me to wake up, but I'd chosen to ignore it. I'd been too busy patting . myself on the back for the great job I'd done, and kicking myself in the pants for the girl I'd sacrificed to do it, to pay attention as I should have.

"Very clever," I said sourly, "but after all, what's the point, Paul? I mean, so you've got the stuff, but you'd have had it tomorrow or the next day, or Mr. Lincoln Alexander Kotko would, as soon as my current chief got around to taking it from me and handing it over. Why make with the guns and helicopters, except to make me look bad?"

"Well, there's that, of course; I don't deny it," Denison said frankly. "Show up the Master at his own game, and all that sort of thing. But that's just a little private bonus. The fact is, this tame naval hero of yours makes me nervous. He's got some odd contacts along this coast, and when I try to check up on him and what he's doing, I meet the goddamndest case of community lockjaw you ever saw. And then, of course, he's made a real point of his delivering the goods to Mr. Kotko, in person. My job h protection, chiefly, and when somebody's all that eager to get into the Presence, I start worrying. Okay, L. A. likes the oil deal, crooked as it is—after all, it isn't every day you're offered a piece of government-guaranteed and government-sponsored larceny—and he was even willing to come to Norway and sacrifice his sacred privacy briefly to put it over. But after he got here, I got a hell of a bad feeling about the whole thing, Eric. Damn it, it smells wrong; and I decided that Captain Henry Priest wasn't really a nice enough fellow to be allowed to associate with my saintly employer, if it could possibly be avoided. After all, look what he just did to you, or tried to do."

"What's that?" I asked. It was one of the things I'd guessed, from the way things had happened, but it wouldn't hurt to hear it said.

"Well, I got this from that same young P.R. man with the FOR SALE sign hung so conspicuously on his nose. I wasn't the first purchaser, you understand. Captain Priest had been there with the greenbacks before me. The deal that had been made between them was, Elfenbein would get the stuff, using his daughter as planned; he'd deliver to Norman Yale and get his money—Aloco's money—as promised; but Yale, instead of handing it over to his bosses at Aloco, would slip the stuff to Priest for a substantial consideration. Oh, they were going to muss him up judiciously, and he'd claim to have been set on by a bunch of desperadoes, probably including you, who overpowered him and took the papers after he'd put up a valiant but losing fight—that gray-haired old routine."

"I wondered what happened to good old-fashioned loyalty," I said sadly.

Denison chuckled behind me. "Your girl—your other girl, the one who got left—is probably asking that question right now, amigo.”

"Forget I brought it up," I said. "So Priest was going to get the stuff from Yale, who'd get it from Elfenbein, who'd get it from Greta here. And what were Mrs. Barth and I supposed to be doing all this time?"

"Getting thoroughly double-crossed," Denison said. "At least your girl had to be, obviously. They couldn't have two pretty young ladies with binoculars turning up at the rendezvous. Furthermore, Yale explained, they needed Mrs. Barth as a hostage, since they might have to trade for the data you were carrying if they couldn't catch you with it." I heard him chuckle again. "I didn't laugh out loud at that, but I wanted to. The amateur mind is delightfully naive, isn't it, Eric? But you'd think a pro like Elfenbein would know better."

"They all watch too many sentimental movies," I said.

He went on: "Anyway, Yale told me that he'd pointed out to Priest that Mrs. Barth had been armed and briefed by you, and seemed to be a tough young lady. Disarming her would get a bit hairy, not to say noisy. Priest said not to worry, he'd take care of it. Apparently he did."

"He did," I said.

"You don't seem very shocked or surprised by his perfidy, Eric."

I said, a bit grimly, "He's a practical man, our Skipper. With Yale on the payroll, he could take his choice, but he had to make up his mind. Should he sabotage Elfenbein with Yale's help, and let me get through to the contact as originally planned? Or should he sabotage me, and get the stuff from the Elfenbeins via Yale? That was the unexpected way to do it, and I guess he hoped it would throw you off if you had any tricks pending—of course, he didn't know you'd bought Yale out from under him. And then there's the fact that I don't think Hank Priest really trusts me. He knows I don't really work for him, but for a guy in Washington. He preferred to deal through somebody he could bribe." I shook my head. "No, Priest doesn't surprise me; but you do, amigo.''

"How so?"

"Why did you bet on me?" I asked. "You had Yale right there. Obviously, after spilling all this to you, he was ripe for the big deal. If you'd just paid him a little more, he'd have double-crossed Hank Priest completely, and brought the stuff to you instead. All you had to do was sit tight and wait for him to drop it into your lap."

"And if I'd done that, I'd still be sitting tight and waiting, wouldn't I?" Denison said. "Hell, man, I'm not a dumb sailor like Priest I'm your old friend Luke, remember? And in the great Siphon sweepstakes, I was going to put my money—L. A.'s money—on the winning nag; and I knew damned well it wouldn't be Elfenbein or Yale or any other half-assed crook. So I bet on you, my reliable old pal Eric, and you came through for me just as I'd figured you would."

I said, "That's very flattering. I appreciate the testimonial, even if it makes me out a horse." It was time to get the conversation away from the Skipper and his odd tricks, so I said, "Incidentally, I just remembered I met another guy named Denison once, a long time ago. He was an F.B.I, man and a real stuffed shirt."

"No relation," Denison said. "No badges or stuffed shirts run in this family.. .. Matt."

"Yes?"

"What's the current word?"

"What do

you mean?" I asked evasively, although I knew perfectly well what he meant. He didn't say anything. I said, after a moment, "Well, if you must know, the word is I'm supposed to take care of you as soon as I can arrange it so there'll be no political backlash."

He sighed behind me. "Goddamn it, that gray bastard in Washington never forgets, does he? So what's to prevent me from getting you out of my hair right now?"

"Not a damned thing," I said cheerfully. "In fact, it's a hell of a fine spot. I recommend it. Just pull the trigger and open the door. No problems, just a nice big splash a couple of thousand feet down. Of course, he'll send somebody else, sooner or later."

"And of course, actually you'll play hell trying to arrange it so L. A. won't light a fire under you. Even if you make it look like an accident, he won't believe it; and he's got more political clout than a lot of Prime Ministers. No, I don't really think you'd better try it. Matt. L. A. looks after his people; and I'm the best he's got, if I do say so myself. I've saved his life at least three times since he put me on the payroll, not to mention straightening out a number of cockeyed deals that might have cost him a lot of money. . . . Well, no sense being hasty. Let's see how it breaks, amigo."

I didn't give a large sigh of relief but that's not saying I didn't want to. The morning's intermittent rain turned to gentle snow as we came over the mainland. The moustached pilot took us away from the coast a bit, wiggled and twisted through some nasty little white mountain passes, and then brought us into a pretty, Alpine-looking valley with a gravel road down the middle, on which the snow wasn't sticking yet. The chopper settled down beside it, among some wet, unhappy-looking cows that scattered to give it room. From there, a driveway led up to an expensive-looking house built onto, or into, the side of the mountain above us, all glass and angles and flying bridges.

A tall man in a long fur coat had been standing on one of the out-jutting porches, watching us land. On his head was one of the high fur hats I associate with Cossacks in winter. He didn't wave any greetings. He just waited until we were down, and then turned and walked into the house, unbuttoning his coat as he went, and pulling off his hat. His head was as brown and shiny and hairless as a hazelnut

The Terminators

The Terminators